Jollying

In an aged care facility when a resident dies the staff become crazy happy. Singing and dancing with the other residents so they don’t see the body leaving the facility. The driving thought is that seeing the body leaving is upsetting and the other residents shouldn’t have to see this. This is ‘Jollying’.

However, the impact is:

- Staff feel silly and have to hide their own sadness

- Fellow residents don’t know what happened to the person – they just aren’t there anymore

- Grieving is not seen as important

- Residents begin to know that the ‘crazy’ act means bad news

- Residents are not given a choice, such as they would have in a family home

- Truth and trust have taken a beating.

In direct care the way staff reacts or handle potentially traumatic events is often not in their control. The service they work for may have a clear policy, such as in the aged care facility example above. The family may also express their wishes on how they want things handled. The individual/s involved may also express certain expectations.

Validation

It is critical that we don’t lose touch with our own emotions and feelings. Or indeed be made to feel the emotions aren’t valid. Emotional validation is important.

This doesn’t mean that you have to agree with the emotion being expressed, it means you acknowledge that their emotional response is warranted.

Validation is not only acknowledgement of one’s feelings but an understanding that allows a person to feel heard and valued. Individuals can provide their own emotional validation or can receive it from others. In the workplace, it is often colleagues and clients who provide this. In some emotionally charged workplaces, such as palliative care, some disability services, nursing homes, some aged care facilities, counselling and support is provided by the organisation. This act is validation of the workforce and individual validation occurs in counselling.

In a disability residential service a child died. The child had lived in the home and been cared for by the same staff for over 5 years. The supervisor was rung and came to the home. On arrival, it was clear that the other four residents were upset and agitate – one in particular had begun to self-harm. The supervisor told the staff members to calm down, stop crying and focus on the other children.

The result was that staff experienced a range of feelings:

- Rejected

- Embarrassed

- Blamed

- Judged

- Invalidated

The supervisor’s intent was to calm the other children; the impact was to upset the staff in different ways. Within five months 50% of the staff in this home left the job.

It is not just staff who require emotional validation but also other residents/clients and families.

Empathy

Maya Angelou, African-American poet and author (1928-2014), said:

“I think we all have empathy. We may not have the courage to display it”

It is felt that nearly all people have empathy, the exceptions being psychopaths, sociopaths and narcissists, but many of us don’t use this cognitive process. There are ways we can learn empathy, or enhance our ability.

In essence, empathy is about understanding things from another person’s perspective – the key word here understands. You don’t have to agree or believe the same thing, you just have to show that you understand and except the validity of emotions or feelings. Relationships thrive with nurturing, care and understanding.

In the disability services example above the supervisor showed no understanding of, or care for, the staff’s feelings. They only focussed on the job to be done.

Showing and building empathy can be reflected in:

- Listening: this means not interrupting but focusing on the person you are talking to; putting aside your own thoughts, opinions and phone and really hearing what the other person is saying.

- Tuning into nonverbal communication, including tone of voice.

- Using the other person’s name and showing them you are engaged through your own body language.

- Not allowing the person’s beliefs to colour your understanding: if you judge a person and allow your findings to colour your interactions, then practicing empathy is both difficult and uncomfortable

- Start giving genuine recognition: move beyond “wow you’ve had a great life” to “I admire your skill in rock climbing and the way you approached the challenges”. Instead of writing “LOL” write “you have a great sense of humour” or “ I love sharing your humour”.

- Broaden your horizons: read fiction. The Readers Digest writes.

“when we step into a fictional world, we treat the experiences as real. …. Reading fiction literally makes you more empathic.”

A study in the Netherlands shows that when a story transports you to a new world you are likely to increase your empathy. The study groups that read a series of news articles decreased their empathy. (Bal, 2013)

In direct care, empathy is usually high and can be linked to compassion. Reading the Blog on Compassion Fatigue (create link) will provide you with more information on this.

Jess recently experienced daily in home nursing care for 4 months. The nurses had a heavy work schedule and did not have a lot of spare time. However, when they talked to her, they continued laying out supplies or reading or writing notes. Jess was going through something new and traumatic and needed to understand what was happening. Jess asked lots of questions, but her need was not being met. Only one nurse picked up on this need: this nurse stopped and looked at her when they talked, explaining when she needed to write or read and why. She picked up the clues. In answer to the question “why was this infusion necessary?” most would reply “your doctors have ordered it and must think it will help.” The truly empathic nurse would explain how the medication was used and the conditions it treated; in addition, she would talk about potential side effects and things to watch out for.

Sympathy

Sympathy is about sharing the feelings of the other person, and is often related to compassion, pity or sorrow. It is a valid reaction and response. However, sympathy doesn’t have the same strength as empathy, because you are sharing a feeling rather than understanding the cause.

Sympathy states “I know how you feel”, whilst empathy states “I understand what you feel”. Whilst the difference is subtle it is worth noting as ‘knowing’ something is based on judgement and your own perspective. Understanding is accepting, thoughtful and empathetic.

Sympathy is often our first reaction when we here disturbing news. It is a valid and meaningful response. The challenge is to stop at the expression of sympathy and not sharing your own story but keeping the emphasis on the individual.

One of the issues direct care workers need to be aware of when feeling and expressing sympathy: There might be a natural tendency to feel sympathy for someone who developed leukaemia, but less sympathy may be shown to someone with an opioid addiction. When the problems are perceived to be generated by lifestyle, the judgement component can come into play. In direct care, this can be dangerous to wellbeing and the environment in which a client is living.

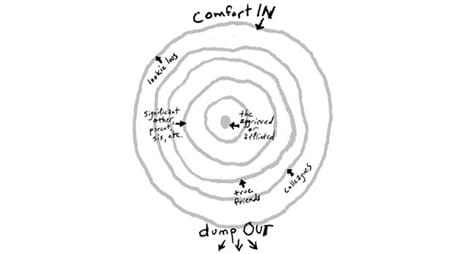

In 2020 Susan Silk, a clinical psychologist, and mediator Barry Goldman developed a “Ring Theory”. The theory recognises that everyone surrounding an event will have negative feelings and emotions but because those most closely affected by the event need comfort not someone else’s grief, they proposed that the venting and sharing of opinions moved outwards.

“When Susan had breast cancer, we heard a lot of lame remarks, but our favourite came from one of Susan’s colleagues. She wanted, she needed, to visit Susan after the surgery, but Susan didn’t feel like having visitors, and she said so. Her colleague’s response? “This isn’t just about you.” (Silk 2013)

In Ring Theory, the colleague who needed to talk would do so with someone in a more outlining circle and only pass comfort inwards. Susan as the person at the centre can say whatever she wants. Everyone else can complain, bemoan, and curse life to people in a more outer circle to theirs. You wouldn’t say Susan looks awful and you hate it to her husband, but you may say it to someone on an outer ring, such as a work colleague.

This is a good easy to remember phrase: Comfort in, Dump Out

It is also worth thinking about timing. When supporting someone when an event happens, lots of people rally and offer support, compassion and sympathy. They can become inundated with flowers in the first few weeks. Grief lasts beyond these first few weeks however, and offering support a month or longer down the track is worth thinking about. A month after my grandmother died a close friend sent me some flowers and it made me feel warm and supported still.

Conclusion

There are many options open to us and the path we follow has impacts both on ourselves and others. In a direct care role we have three drivers:

- The client or person we are dealing with

- The policy and procedures of the employing organisation

- Our own personal believes feelings and skills.

Direct care workers are working with people in less-than-ideal situations that they have not chosen. They deal with death, debilitating illness, pending death or disability, loss of capacity and change of personality more often than the general public. Empathy is a highly utilised skill in this type of work.

References

The Netherlands Study: Bal PM, Veltkamp M (2013) How does fictional Reading Influence Empathy. http://doi.org/10.137/journal.pone.0055341

Click here to learn more about our Health and Direct Care workshops.